By Caleb Taylor

One of the biggest debates in Christian churches today has to do with full acceptance of LGBTQ+ people in the pews and the pulpits. Not only are denominations poised to split over the treatment and ordination of LGBTQ+ people, there’s even a documentary called 1946: The Mistranslation that Shifted Culture arguing that the English word “homosexual” should not be in the Bible at all. The film made it into Indie Wire’s “DOC NYC 2022: 10 Must-See Films at America’s Biggest Documentary Festival” and has garnered a fair amount of publicity. [Watch the trailer here.]

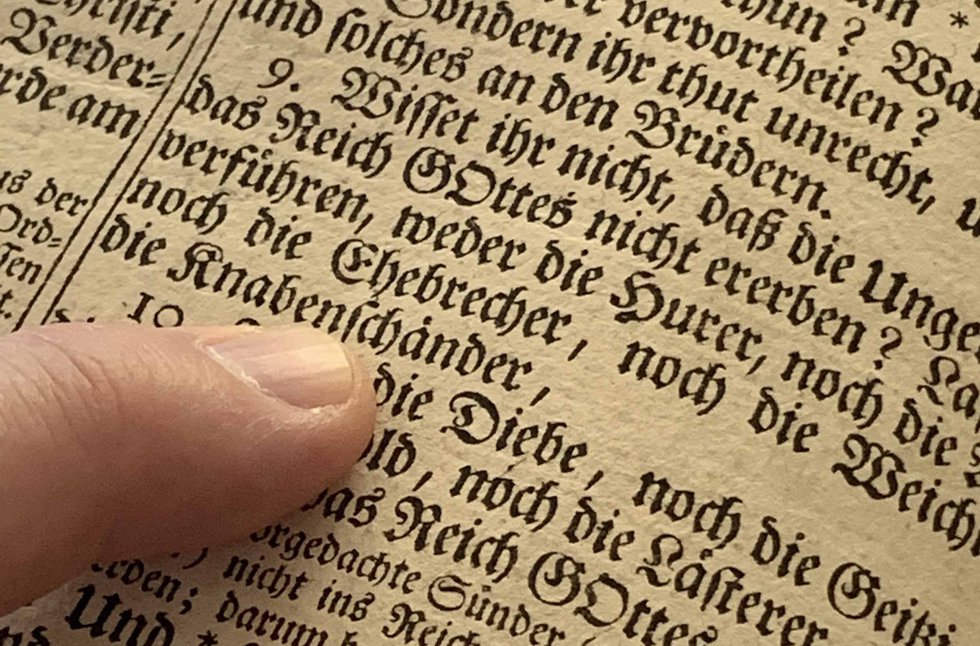

The argument goes that in 1946 the team working on the Revised Standard Version (RSV) mistranslated the Greek words malakos and arsenokoitēs as “homosexuals.” Malakos typically means something like “soft” and was, at times, used euphemistically. Arsenokoitēs is trickier because it occurs so infrequently with such little context that it is very difficult to pin down its meaning. Still, the translation in the RSV (specifically in regard to 1 Corinthians 6:9) was passed on to most biblical translations produced in the following years.

Those working on the RSV, however, were not the creators of anti-homosexual bias. Criminalization of homosexual sexual activity goes back to at least the 1500’s as the Human Dignity Trust succinctly depicts. And, that is just in English law. Sodomy Acts criminalizing homosexuality were well established long before the 1946 RSV translation. Moreover, “sodomy,” the word from which the Acts derive their name, comes from the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, which alludes to sexual abuse but has been used by traditionalists to condemn homosexuality. Thus, even if the word “homosexuality” did not appear in English translations of the Bible before 1946, the powerful did not need it to oppress LGBTQ+ people.

Translation is important, but using the correct words will not fix the “problem.” Nor will correcting a few words deter the will of the powerful who benefit from the suppression of LGBTQ+ people. There is the text, and then there are the communities that utilize the text. The group gives meaning to the text, and as long as the power structure of the group is built for suppression, it doesn’t matter what the original writers meant. Dismantling the power structure must take priority; otherwise, we’re doomed to the fate the Anabaptists suffered during the Reformation.

The Anabaptists insisted on a particular translation of a particular word in the Bible as well. And, though their issue may seem innocuous today it was tantamount to breaking down the social order of their time, much as anti-LGBTQ+ people claim inclusion and diversity would do today. The Anabaptists believed that the historical and linguistic evidence pertaining to baptism clearly indicated that the ancient Greek word baptizō meant “to be immersed.” Further, they believed immersion was a choice that should be made by people old enough to make major life decisions. In other words, they thought that when people are baptized they should make that choice for themselves and be dunked as opposed to being sprinkled as babies because their parents and society made the choice for them.

The Anabaptists’ conclusions were entirely reasonable. In fact our contemporary dictionary definition of baptizō is “1. to dip repeatedly, to immerse, to submerge (of vessels sunk) 2. to cleanse by dipping or submerging, to wash, to make clean with water, to wash one's self, bathe 3. to overwhelm.” Further, almost every example of baptism in the Christian Bible is of an adult making the choice for themselves (though there are a few families who are baptized together).

Still, even though the Anabaptists were academically correct, they failed to win the social battle and suffered greatly for it. As a result, they were often forcibly immersed to death (drowned) by those who favored infant baptism. Infant baptism maintained civil religion and codified the divine authority of rulers over their subjects. If people could simply choose as adults whether or not they wanted to be under the authority of the church, that would greatly diminish the power of the ruling class. On the other hand, if everyone was baptized into the church as infants, the ruling class could govern the lives of their subjects with divine authority from birth to death.

It wasn’t until many years later, when Anabaptists were able to escape to far off lands away from the hold of monarchs that their ideas about baptism would become more popular. They had to find a way to operate outside the power structure or dismantle the power structure before their ideas could openly come to fruition.

Similarly, it is the power structure among Christians and politicians who desire to leverage the Evangelical vote that creates the “problem” with LGBTQ+ rights. Proper translation did not help the Anabaptists’ cause, nor will it do much for LGBTQ+ rights. There is a constant stream of academic debate over numerous issues within biblical texts that remain comfortably hidden away in the realm of academia because they are of no consequence to the power structure. Controversies over translation only break into the headlines because the powerful wield those words as tools of suppression. If they did not have those words in the text they would use (and do use) other texts and lines of reasoning.

In many denominations, straight cis women are still unwelcome within the power structure. Within the Churches of Christ and Independent Christian Churches women, often, cannot be ministers, and when they can in most cases they are barred from the highest positions such as Senior Minister or Elder. Such is the case with other denominations as well, including the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches. If many Christians are reluctant to open the power structure to people they deem “natural” creations of God, they are definitely not going to open it to people who, in their eyes, dismantle the entire natural order of creation, no matter how we translate a couple of ancient Greek words.

For those of us who are members of religions with sacred texts, those texts are incredibly important for shaping our identity not only as members of a particular religion, but also as socialists. I have personally devoted nearly half of my life to the academic study of the Christian Bible. Our texts have so much wisdom to share. Those who participated in the scripture-creation process (writers, editors, redactors, compilers and so on) were often directly addressing the power structures of their time.

We continue that tradition as we read and interpret our scriptures, moving from written word to collective action that seeks to build a more just and equitable society. As socialists, we can be people of the text in full knowledge of how our texts are leveraged as weapons for oppression, suppression, and abuse. We can stand in the way of those who would use our religions as “the opium of the people,” and work to help our fellow believers come together in equity, justice, and love. We can stand together to represent the socialism of the divine in which we partake. Good translations will come as we continue the work of solidarity, but let us hang our work of solidarity on love for one another rather than linguistic debate.

Caleb Taylor is a dad, husband, and writer. He has an MDiv. from Harding School of Theology and is a member of the Institute for Christian Socialism.

Image credit: The Forge Online Photo